How Ukrainian fashion photographer Vera Blanche documents the war

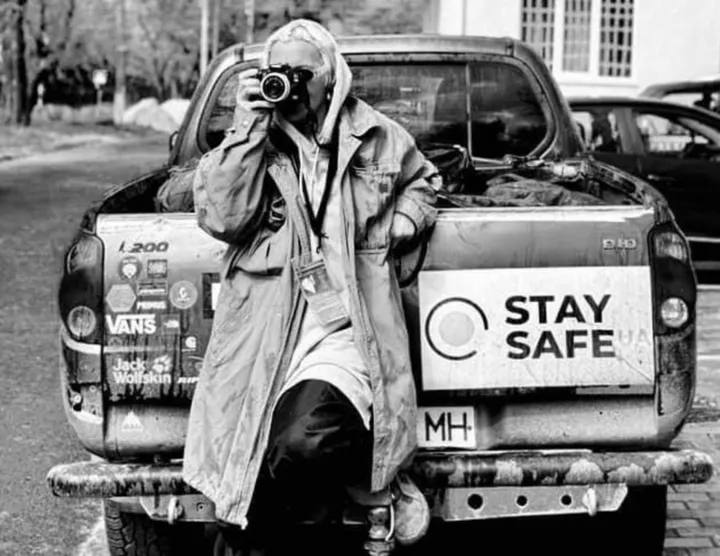

"Philanthropist. Artist. Photographer" — written on Instagram by Vera Blanche. It is in this sequence. Vera Blanche from Kyiv is a well-known Ukrainian fashion and art photographer who has shot for Vogue, Dazed and Confused, Fucking Young, Harper’s Bazaar, and L’Officiel and collaborated with fashion brands. Vera graduated from Central Saint Martins College in London and loved to shoot fashion and portraits of people. But with the beginning of a full-scale invasion, the girl received accreditation from the Armed Forces and went to the front to document the war. We recorded her story.

The first week after the full-scale invasion, I didn't shoot anything: I just sat in a bomb shelter or my bathroom, reading the news and being horrified by the sounds of artillery and machine-gun fire around Kyiv. It was impossible to do anything. And in a week, when I got used to sirens and shots to some extent, I realized: stop, it's time to do something.

I picked up the camera and went to look outside. Kyiv was empty, there were no people. And there was an unspoken law: if you take a camera, you are immediately an enemy — like a stranger among your own. So I realized that I needed to be accredited as a military photojournalist. Went to Lviv, and received accreditation from the Armed Forces. I filmed Lviv and refugees a little bit — in those days the station was like an anthill, like the Maidan in 2013. So many people! I stopped in Frankivsk and Chernivtsi, recovered a little, and was inspired by the strength of my friends who volunteered there and returned to Kyiv.

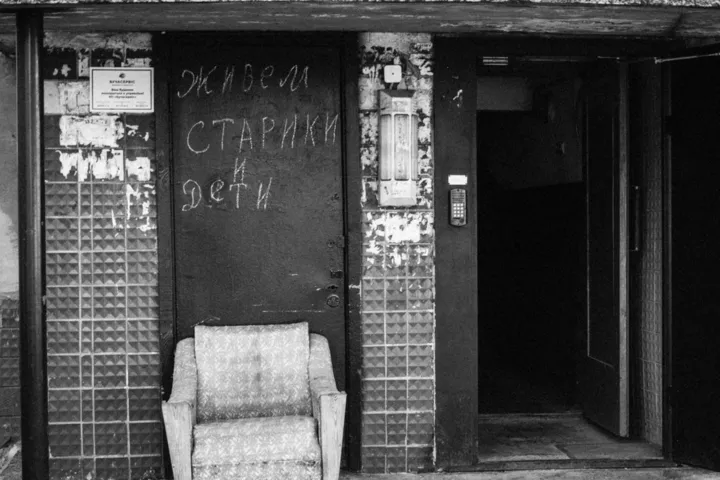

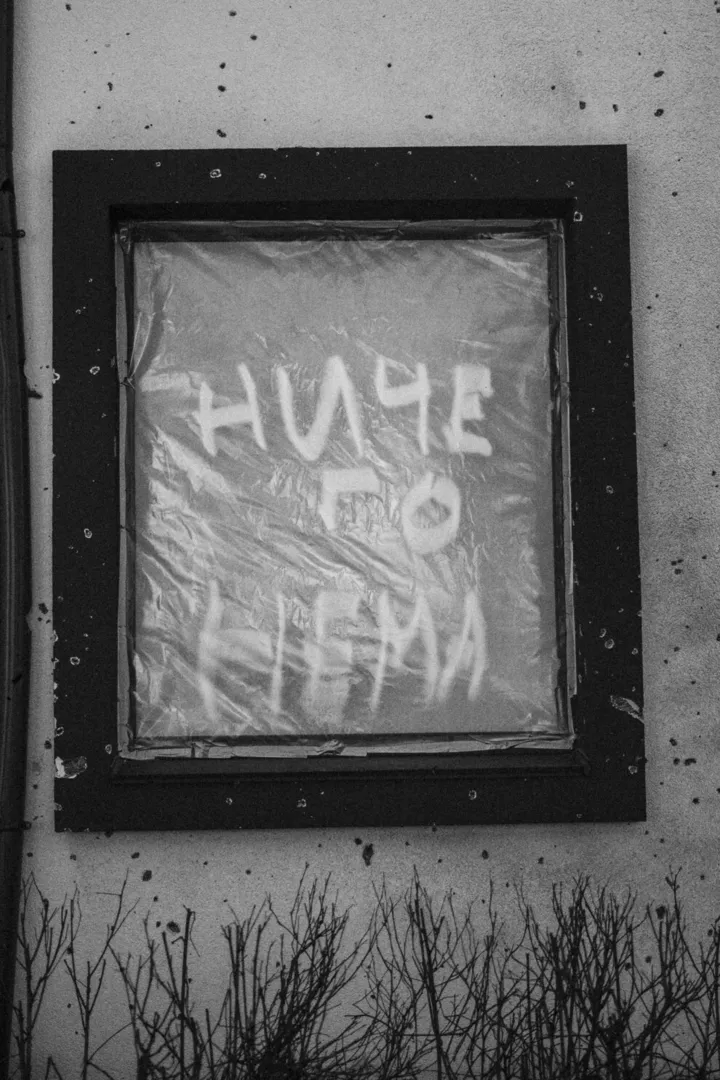

Unsurprisingly, Kyiv was one of the first military cities I filmed. It has changed a lot since the beginning of March when I left. Became like a fortress. Checkpoints on each side. This is not the city I left – it will be ready for battle. I drove in, saw burnt cars on the Zhytomyr highway, destroyed houses on Nyvky — that's how I saw the war for the first time. Then I felt a gag reflex. I could not believe that this was happening in our Kyiv, in our country.

Then he went to the Kyiv region. This was when racist troops were still standing on the Zhytomyr highway, the last days before the occupation. At Petrushki, it seems, got into a direct battle: artillery, artillery…, and then the machine-gun turn begins. But we are already used to it — I heard it in Kyiv as well. But don't even worry – you're just doing your job.

One of the first times we came to the Kyiv region with criminal investigators was when they took the bodies of tortured Ukrainians. We have witnessed this, filmed this horror. The feelings were difficult, and it was still very cold, even inside – because it is unrealistic to realize that a person is capable of such atrocities. There were not just people killed. They were tortured, they had no limbs, they had their eyes gouged out, they were cut, they were burned. Then Irpin, Borodyanka. The road was difficult, cars got stuck, stuck in this mud, and we pushed them.

I remember my feelings in the beginning. You drive through Borodyanka, and it seems to you that this is the scenography of a war film. Or when you take pictures of damaged houses and know that there are still people under the rubble waiting to be rescued. Feeling this pain — I do not know how to eradicate it from myself.

And the land — I will never forget it. You are constantly walking on the black scorched earth. Instead of streets – a solid black emptiness.

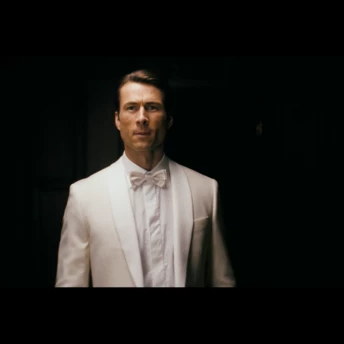

The first time I had the opportunity to shoot the military, I shivered. Because I understood that now I am touching our shield, our heroes, warriors of light! They are superhumans, they hold the peace of this world on their shoulders. And mine, and yours, and the peace of Ukraine, and the peace of the Western world. They keep the peace of the civilization that has been rebuilt for centuries by all mankind and for which we all stand.

Later, when I spent more and more time with them, and went further and further, to the east, to Slovyansk, Bakhmut, and Kramatorsk, they became my brothers and sisters. Like a family. And I felt that they were taking care of me. For example, I wanted to go to take pictures at the ceramics market in Slovyansk. It's still a yellow zone, but I was always accompanied by a convoy. I just felt physical how they protected me — even more than necessary (laughs).

These are people you want to worship. Hug. Interestingly, people in the rear often ask me to hug the soldiers. Especially women (laughs). And there, on the front line, the guys always send a big hello to the whole rear. They are very grateful and say: if it weren't for the rear, we wouldn't be here.

I can't say I'm not scared. Scary, of course. Now I even have a "rotation" — I took a creative break to go to the art residence and prepare for the exhibition in Chernivtsi, which will then be shown in Europe and America. This is a cultural front, and we have to work on it. But now my brothers are already calling me to Kramatorsk (laughs).

Sometimes I feel fear and discomfort. In the east, when you drive on empty trails, and only rare cars around. And there are no civilians — either military, humanitarian aid, or ambulance. The blood sometimes runs out. Especially when I first went east, to Slovyansk, in an ambulance, not even realizing what was waiting for me.

Fear is often nearby. Being there, on the front line, you can't even go to the store by yourself. You go with an armed soldier. The only way. Or when they say: maybe at night, we'll be surrounded, so we will leave. But you understand: if there is a retreat, you are not going to the rear. It hasn't happened yet, but you feel horrified…

Even when I'm in a safe place, I'm afraid that someone might kidnap me or throw a grenade at me, because I'm a military photojournalist after all. It may be pointless, but it is. Even when I think about going to Europe and meeting racists there, it confuses me. I feel the danger of racists. Wherever they are – in Paris or Berlin.

This inhumanity, which we see in the enemy, destroys us from within, destroys us. At the same time, the humanity we see in other people is fascinating. After all, every time we meet the heroes. For example, on the front line, you see a Japanese paramedic who came to rescue Ukrainian boys and girls. And he runs there, to the front, under fire, to pull out the wounded. And you understand that this step of his may be the last – but with this step, he gives others a chance at life.

One day we were taking a severely wounded soldier from Kramatorsk. The lungs were punctured and a fragment of a shell got stuck a few centimeters from the heart … After all, this is an artillery war, and the injuries are very severe. He was bleeding. Go 20 kilometers. And the doctor above him, like an angel, supported him and did not let him sleep. Just like an angel.

And in the rear — everyone is trying to help. And it brings me back to life.

In early April, we went to Moschun. We drove just along with the ruined villages. All around you is a black solid spot instead of the houses where people lived and prospered a few months ago. The sun was already setting, getting dark. It's not dark yet, but almost everything around is black. And suddenly, very slowly, people come out of this black landscape. These were locals who had been there all this time, in the occupation … We went with a humanitarian convoy, brought them food, flashlights, water — imagine, they were in the occupation for a month. And they say, they say, we do not need it, give it to someone else. In Russia, a mug is beaten for a package of sugar, and in our country, people are always ready to share the last.

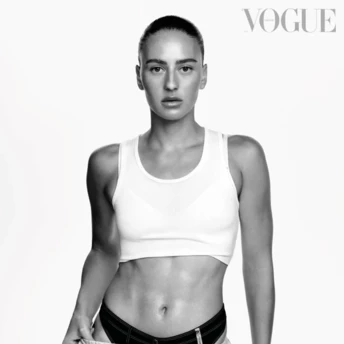

Of all the things I can photograph, I am most fascinated by the human face. Not so long ago I was in Chernivtsi and saw a beautiful girl on the street. She stood and washed the gallery window. It turned out she was a model. I fall in love with beauty, with men and women, I love beautiful people – so I just offered her to shoot in the studio.

I then thought this is about what? I think I wanted to feel the beauty again. I wanted not destruction, but beauty. After all, beauty is inspiring. I generally think it's all for the sake of beauty. We win for the future, for life, for beauty. We must rebuild our Ukrainian DNA — creative, sincere, real, talented. We have to raise it.

A friend recently asked me if fashion would be relevant after the war. Or beauty? Of course! After World War II, women drew black pencil arrows on the legs behind, imitating stockings. For the sake of beauty. For the sake of life.

I am glad that I chose not to go, not to leave my country. I chose to be near the wound of my country. That's why it was a chance for me to stand next to my soldiers and make a film. It is extremely important to show it. Today, the recent history of Ukraine is being written: through blood, through victims, through war. We are writing a new history of the world. It's an honor for me to stand with the camera and broadcast it.

I am glad that I found the inner strength not to take the bus to Berlin, although the temptation was very strong. When all your friends go to that station in Lviv and say to you: Vera, goodbye! And no matter how much you want to be safe, you return to Kyiv…

Photographer, artist, videographer, designer, director — everyone on the cultural front is important now! Each of us does his job. This is our volunteer movement – we are all looking for ways to be heard, to tell the whole world about Ukraine, and to be given more support and shelter. That Ukraine had a chance to win!