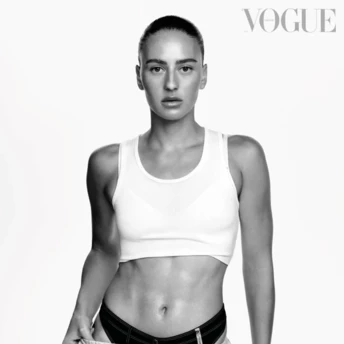

Women of Steel: Natalka Zarytska, Wife of an Azov Fighter, on Captivity, Struggle, and the Future

Ukraine’s bravest women — wives and mothers of prisoners of war — talk about what motivates them to fight.

The first heroine of the project we are implementing together with the Heart of Azovstal NGO, which is part of Rinat Akhmetov's Steel Front military initiative, is Natalka Zarytska, the wife of a soldier of the Azov regiment Bohdan Zarytskyi. Bohdan spent 82 hellish days defending Azovstal and then almost five months in captivity in Olenivka and the Donetsk pre-trial detention center.

Bohdan Zarytsky was released on September 21, 2022. In an interview, Natalka recalls how, during the prisoner swap in the Chernihiv region, she stared at everyone who got off the bus that evening, but Bohdan was nowhere to be seen. She didn't recognize her husband right away. Charismatic, impressive, handsome athlete, 190 cm tall, he weighed 113 kilograms before he was captured. In captivity, he lost 43 kilograms.

We have recorded the story of Natalka and Bohdan Zarytsky.

"Our story began with a book."

It all started with a book. We met in 2019 when Bohdan was already serving in Azov. I was helping different battalions as a volunteer and one day, I texted him: "How can I help?" Bohdan asked for "pens, pencils, and a few books from the home library." I sent him a package in which I put Nassim Taleb's Antifragile. Since then, he and I have shared hundreds of books.

We also shared our favorite fiction, from Puzo’s The Godfather to Remarque’s The Road Back, as well as non-fiction, such as Taleb’s The Black Swan and History of Ukraine-Rus by Arkas. Books toughened us up—I remember reading Castaneda’s Journey to Ixtlan, in which the author tells about his apprenticeship with the Yaqui shaman. Castaneda's opinion is this: an average person has one or two instances in their life when the universe stops—but to whom much is given, much will be required. When destiny wants to level you up, it doesn't just give you one difficult test but several. So it happened to Bohdan and me throughout our lives.

Bohdan was born in the Sumy region. He served in the Marines and joined the Azov in 2018. We have never had a peaceful life: he was in Mariupol, and I was in Kyiv. I spent my life on the train to Mariupol—on Friday, I would leave the office with a backpack, go to the station, and travel to Bohdan. On Monday at 6 a.m., I would come back and go straight to work with my backpack. We always dreamed of getting on a train, going somewhere together, and never saying goodbye. Those train station goodbyes are the saddest thing that can happen to you.

Before the full-scale invasion, the last time we saw each other was on February 14—we spent Valentine's Day together. Bohdan saw me off at the train station. On the outskirts of the city, you could already hear that hostilities had intensified. There was a glow in the sky. "The end of this road—and there is no more life," said Bohdan.

"I went beyond the limit…"

My husband's call sign is Mezha (Limit). Once, the children at school asked my son why ‘Limit.’ And I told him: so that later I could say that I went beyond the limit.. [Play on words between Ukrainian phrases for ‘to get married’ and ‘to go beyond the limit’]. Bohdan often says: I like limits because you can go beyond them.

I was preparing for the war. Back in 2014, I wanted to join the armed forces, but my son had just been born then, and my father was seriously ill. Since I couldn't join the army, I became a volunteer. One day, I asked my father for a hose to supply gas for cooking at the front. I imagined that you could just take a hose and pour the gas through it. He said, "Darling, what sorts of things have you gotten yourself into?" I went to the market, where they cut 10 meters of hose for me... Only then did I admit that it was for the front.

A few years ago, I had serious surgery, after which I was not allowed to lift more than 3 kg. And I weighed 20 kg more than now. Bohdan said: "If you want to get back in shape, you need a barbell." I said, "Me and a barbell?" But a year later, I could lift 115 kg, participated in the European powerlifting championship, and ranked first in my weight category.

Since we met, I’ve been helping him learn English [Natalka is a teacher by training], and he's been helping me build up strength (laughs). When I came to the gym, the guys asked, "Why are you pressing 50 kg?" And I said, "Because an SPG-9, a tripod-mounted anti-tank grenade launcher, weighs 49 kg, and I have to lift it." I was planning to join the army and dreamed of applying to Azov.

When the full-scale war started, I decided to enlist in the territorial defense forces. Bohdan calmly said, "Armed Forces is better," but then asked me to stay home. "You will help me more in the rear," he said. So I did. But I did not leave Kyiv. Yes, I knew what could happen to a wife of an Azov fighter if the Russians invaded the capital. I was ready to defend myself. I remember having a Zoom with my colleagues one day. Internet connection was poor in the basement, so I climbed upstairs. My house is on the outskirts of Kyiv, and you could hear explosions. Worried, a colleague asked me, "What is that?" "Explosions," I said. "Natalia, haven’t you left?" he asked, surprised. "No, I haven't," I said. "The walls are still standing; I'm waiting for my husband. Besides, his fellow fighters know they can always get food and do laundry at my place."

"You have to fight—there's no time to cry."

Last April, when Bohdan was already in Azovstal, I received a message from him: "Natalka, we bury our fellows every hour, shells explode right next to us, we have no medicine. It’s the end. We are doomed."

And I thought, what do you mean—the end? No, we have to fight—there’s no time to cry."

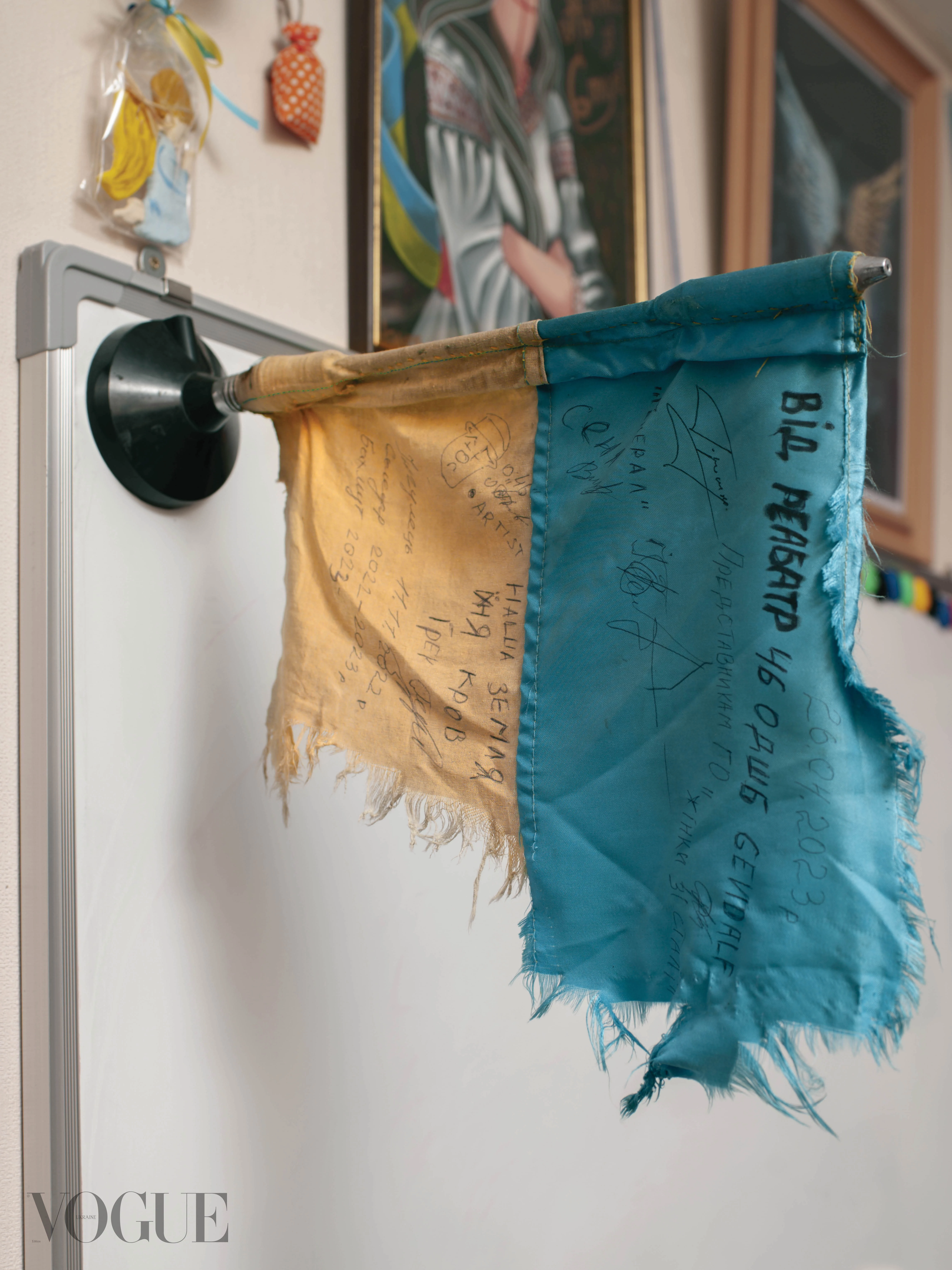

We texted each other every day, and even if there was no signal for two weeks, he would later get a hold of Starlink, and I’d get 200 messages at once. When he texted that they had received orders to stop defending Mariupol, I felt relieved. I realized that we’d manage to raise the awareness of the global community about it and that the Russians would not shoot them down when exiting Azovstal. Yes, it was a road from hell to hell, but it was a change. At least some hope for life. Until a whole barrack of war prisoners was killed in Olenivka. I did not know then whether Bohdan had survived or not.

Later, I asked, "Bohdan, which was worse: Azovstal or captivity?" He said, "Azovstal." There was a sense of complete doom, while captivity gave some hope. All captured soldiers hold on to one thing only—the knowledge that Ukrainians do whatever they can to ensure their release. In Olenivka, there was a TV in the kitchen, and the cooks talked about my interview they saw in which I said that I was fighting for the return of my husband, and they told Bohdan about it.

He wrote me a farewell letter when he was leaving Azovstal. 13 pages by hand, on yellowish paper, by pen and pencil. At the beginning, he wrote: ‘Read until this point, and then put it aside. Read on only if there is no contact with me at all or if you know for sure that I am dead.’ I did not read any further.

‘If I survive, we will read it together one day,’ he wrote. I brought it up recently, but he said, "No, we shouldn't…"

"There must be a buffer between the relatives of war prisoners and the government."

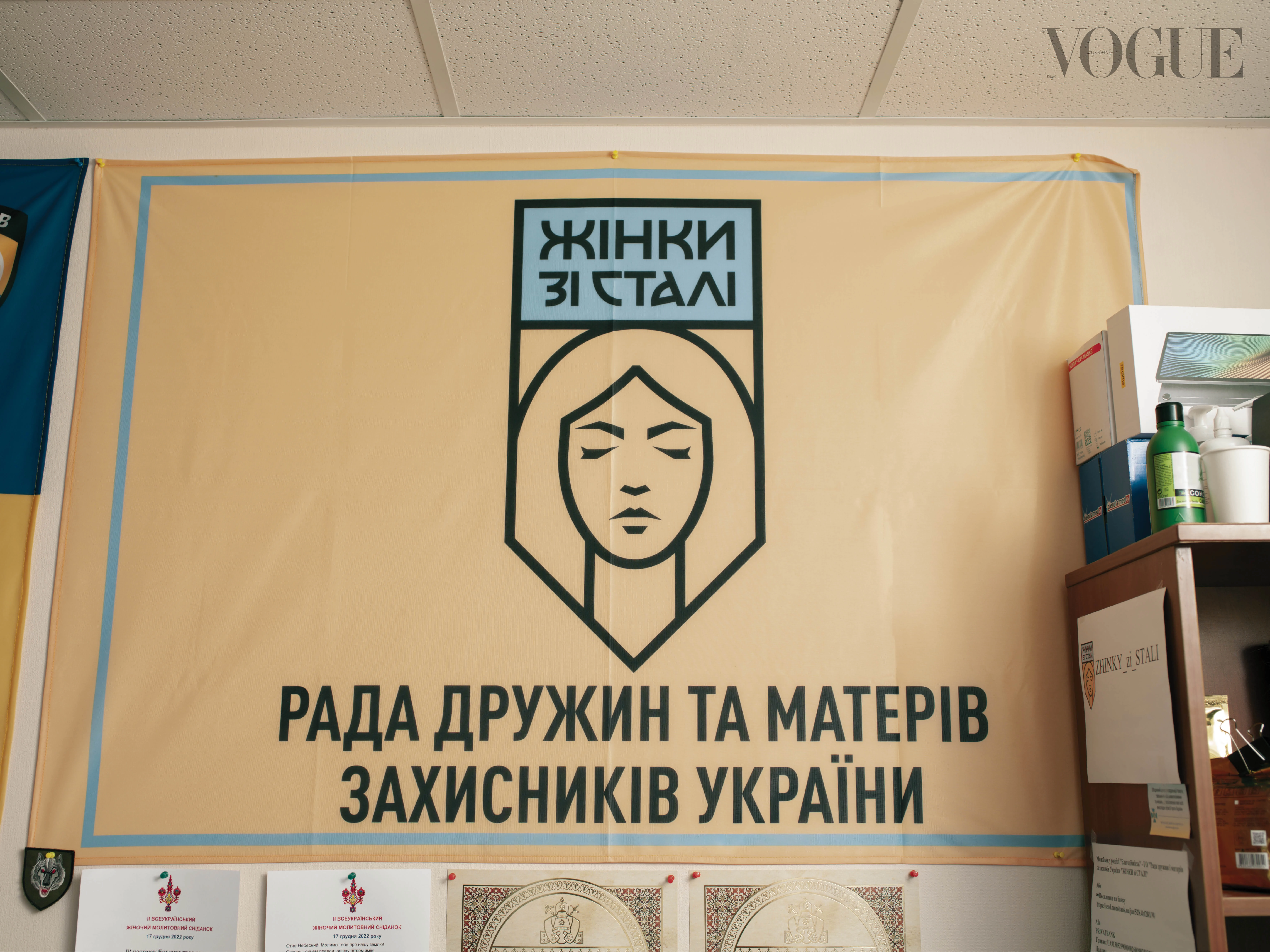

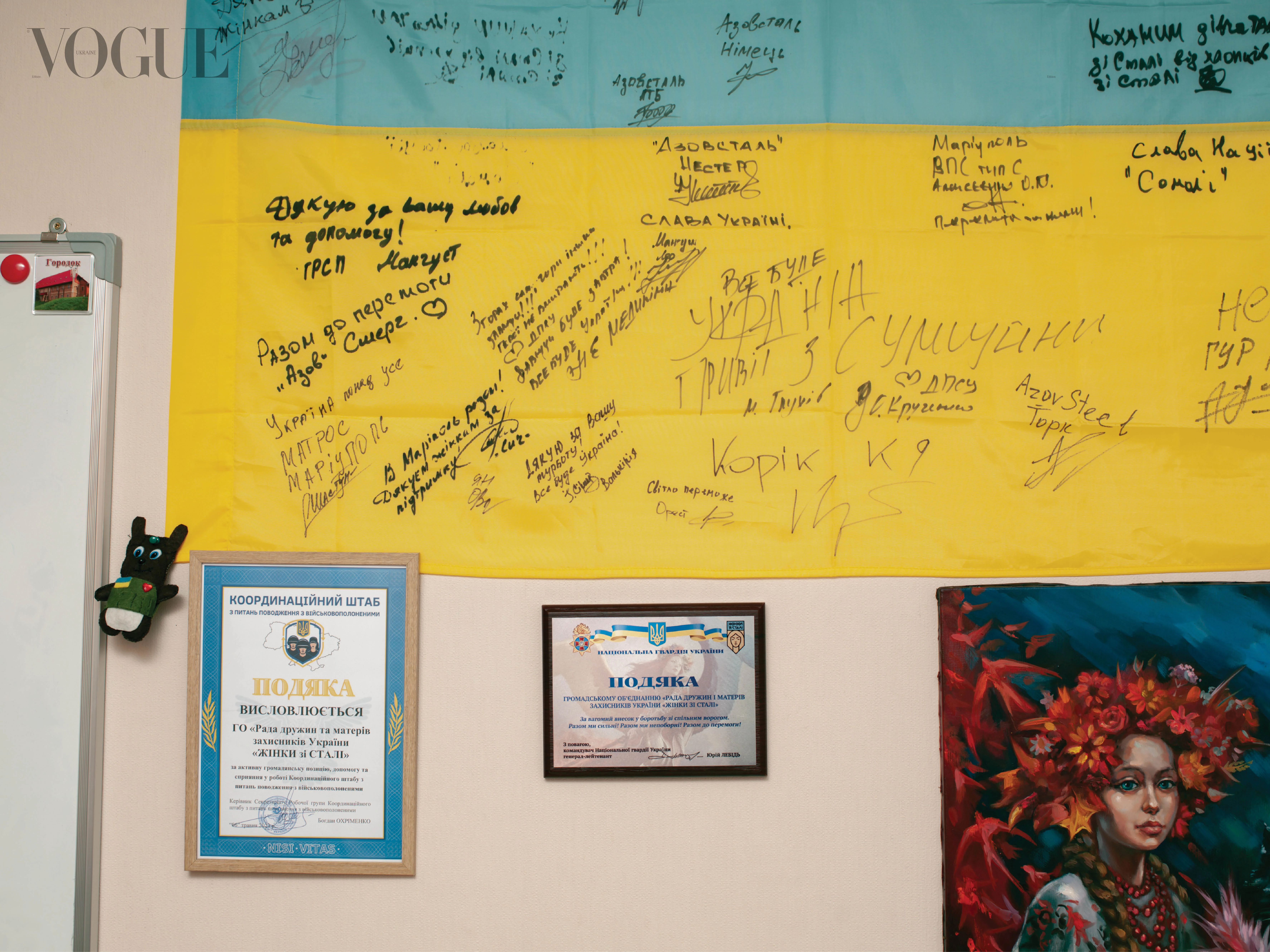

On June 1, we set up Women of Steel, an NGO that was one of the first to start talking to the whole world about the urgent need to save the defenders of Mariupol. My son drew a Save Mariupol poster in May. We took a picture of him holding it on the Maidan, and I posted the photo on Facebook. By the morning, this post had gone viral.

The value of our organization is that it has been set up by the families of military officers. These are very strong women—can anyone be stronger than a warrior? No one else but the mother who gave birth and raised him and the woman who was always there for him. We realized that there should be a buffer between the relatives of the war prisoners and the government, plus it was necessary to generate solutions together.

Today, we focus on two main directions. The first is what to do if your loved one is captured, disappears, or dies. The second is an action plan for those who return from captivity. Yes, there are international algorithms and recommendations from the US or Israel. However, we ourselves, unfortunately, have now a unique experience of dealing with people who have returned from captivity. We have to build on it and extend it.

Several organizations take care of prisoners from Azovstal as well as all other war prisoners and MIA. This is important because our government is just beginning to reorient the country towards a wartime footing—there is enough work for everyone. We, in turn, cooperate with the Heart of Azovstal NGO, and our cooperation is very effective. They are not afraid to listen to us and to hear us—not only to listen but to resolve our needs. For example, Heart of Azovstal gives former war prisoners high-quality digital boxes—with laptops, watches, and smartphones inside—and runs rehabilitation camps for them and their family members. It is crucial that these camps also offer medical rehabilitation, which the government is not yet able to fully provide.

When men and women are released from captivity, they first have three questions: does Ukraine exist, is Kyiv still standing, and what is the dollar exchange rate (laughs). That's why Bohdan put together a booklet, What Happened While We Waited for You, which we distributed along with humanitarian aid through the National Information Office. Imagine being cut off from the world for six months or a year—they don't know anything about what happened while they were in captivity.

We recently presented the Verkhovna Rada committee with a detailed plan outlining the steps for post-release recovery, encompassing treatment and rehabilitation as well as reintegration measures. An important point is social rehabilitation: civilian employment and training for those who are not ready or able to return to military service.

We have partnered with several potential employers. We are talking to them about how they can prepare their employees for the return of former combatants to their teams and how they can support those who have fought and are now back. The companies are ready to develop procedures and make this ‘onboarding’ as smooth as possible. We have also conducted focus groups with those returning from captivity to find out what they need and what kind of attitude they expect in the workplace if they plan to work civilian jobs in the rear. And all the former prisoners of war said, "There's no reason to make any concessions at work or offer extra lunches or something. It's humiliating. We are back and want to forget it and live like normal people."

Overall, I am sure that the military is a great asset in business. They have a good reaction and intuition. These people have a gut feeling about what is going to happen. I trust my husband's intuition a lot. I don't know how he does that, but he senses air alarms and shelling.

"After the captivity, they feel like they are sleeping. They can't believe they are free."

I remember Bohdan getting off the bus during the prisoner swap wearing long underpants, a Metinvest T-shirt, and size 37 slippers that Russians gave him instead of his size 44 shoes. In the queue for backpacks with humanitarian aid, Bohdan was asked: "What size are you?" "XXL," he answered without a second thought. But they looked at him and gave him an M because instead of 113 kg, he weighed just 70...

The General Staff is only starting to develop a concept of how the treatment and rehabilitation process of former war prisoners should work. Currently, they get two weeks of rehabilitation in Sanzhary, but this is not enough. Experts say that the period of the traumatizing event should be multiplied by two to get an approximate ‘half-life’ of trauma. If someone spent six months in captivity, it takes a year for the trauma just to ‘half-disintegrate.’ We are asking the government to introduce a distinct status—a military officer released from captivity. After all, many of those who have returned from captivity want to return to the front line ‘tomorrow.’ But is that even possible?..

Bohdan spent almost five months in captivity—first in Olenivka, then in the Donetsk pre-trial detention center. After he was released, he was diagnosed with vision problems, bilateral dull hearing caused by blast injuries, slipped disks, hormonal imbalance, kidney problems, and PTSD.

We have been talking openly from day one. The first week, I asked, "Did they rape you?" "No, there was nothing like that." "Did they beat you?" "They did until I passed out," he said. Bohdan said that after such severe beatings, you usually hoped to be thrown into a cell and get some rest, but he was thrown into a cell with welded fittings instead of cots, only 10 for 27 people. So, he was forced to stand up for hours.

However, Bohdan says that the greatest torture was hunger: "You hold up for a month before you start passing out." Apathy kicks in. You just lie there and slowly die. You even have a hard time getting up and going to eat because you know you're burning more calories walking than you'll get from food.

Bohdan still has trouble sleeping—he can't sleep for more than 4-5 hours. It helps when he sleeps on the floor at home. It took him three months to start eating normally. And recently, when I was tidying up the papers on his bedside table at the hospital, I found two receipts for cakes, one for a kilogram, the other one for two. "Bohdan, but your blood sugar is 7!" I said. But he just wants it and can’t help himself.

I like to watch him eating—he enjoys every bite. You should see him drink coffee and enjoy the aroma! He was actually doomed and now appreciates every moment. We don't waste time: we live and love despite the war.

I think it all depends on perseverance and mind power. Azovstal is a horror, but why have we been given this suffering?.. Viktor Frankl's approach resonates with us: he says that everything has meaning, including suffering. Our goal is to help others, to tell the whole world about it.

About the Heart of Azovstal NGO

Heart of Azovstal is a project that provides comprehensive support to the defenders of Mariupol who defended the city from February 24 to May 20, 2022. Heart of Azovstal is part of Rinat Akhmetov's military initiative, Steel Front, which supports the Ukrainian military.

Text: Daria Slobodianyk

Photo: Vic Bakin

Video: Yulya Dahl

Make-up and hair: Dima Grushkivskiy