"People want to see a world without wars, but some still like to see violence": an interview with the artist Alevtina Kahidze

Artist, curator, and gardener Alevtina Kakhidze was born and raised in the Donetsk region. Today she lives in the village of Muzychi in the Kyiv region, and her numerous works, shown at international exhibitions, can be seen all over the world. Talking to the world in the language of art, a possibility of a world without wars, and the terrible days in March near Bucha—Alevtina speaks about all that in her detailed interview with Ukrainian Vogue.

This feature was produced with support from the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation's Museum of Civilian Voices. It opens a series of video interviews where our heroes and heroines tell their war stories for the world to hear.

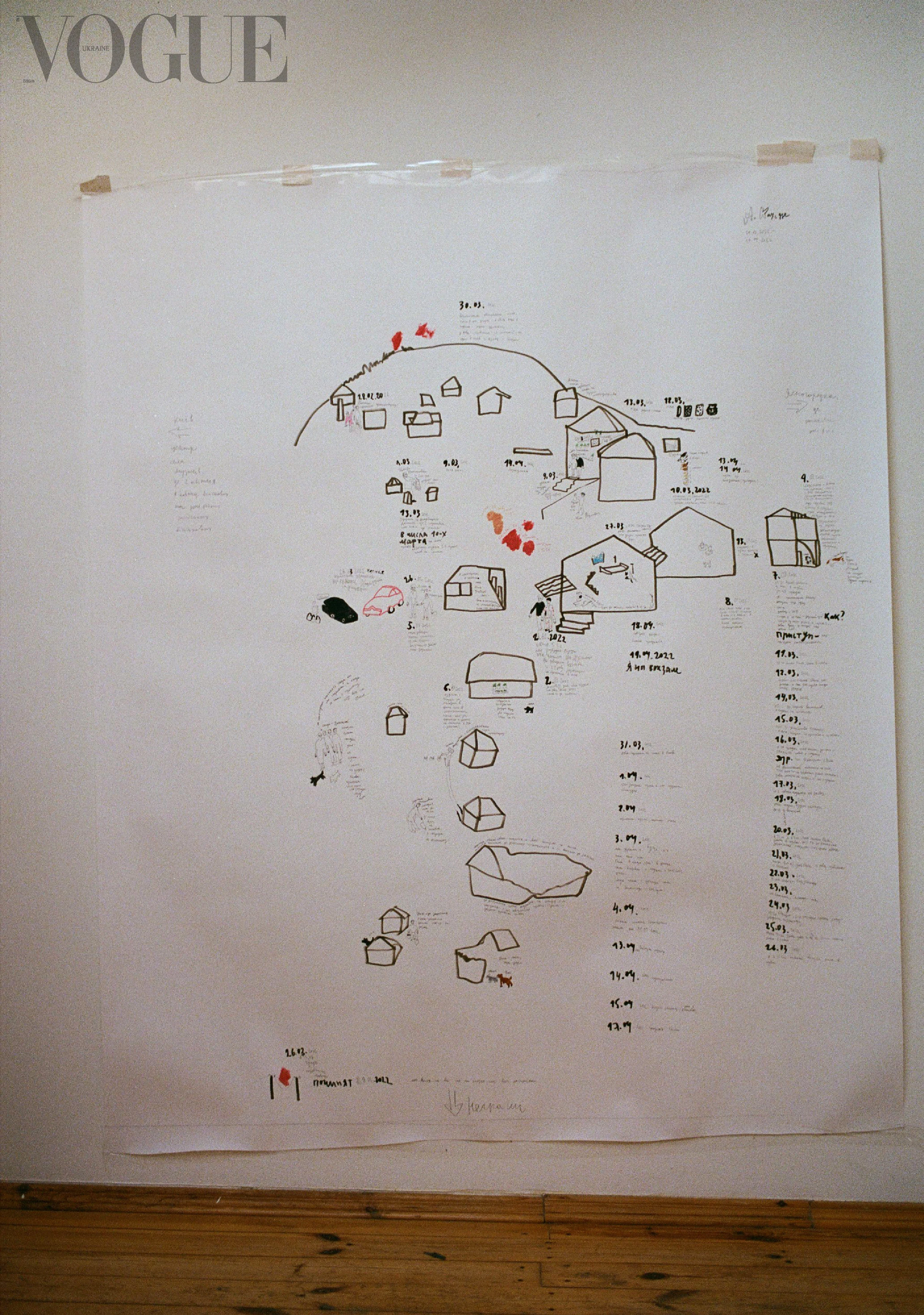

A map Alevtina Kahidze created hangs in her workshop. It shows not just clearly outlined buildings but also red and yellow spots. In this way, the artist has recorded powerful explosions—from February 24 until the liberation of the Kyiv region by the Ukrainian armed forces. These are entries from her diary transferred to the map showing her house, yard, and surrounding houses in Muzychi in the Kyiv region, a village just a few kilometers away from the settlements occupied by the Russians.

Her famous drawing "Bucha. Me. 47 Minutes by Car", with a bloody stain symbolizing the captured city, is an eloquent reminder of those terrible weeks.

During the weeks of fighting in the Kyiv suburbs, Alevtina stayed home with her husband, their cat Penelope, and three Alabai dogs: Bukovski (Buka), Salvador, and Suzy. It was Buka who woke up his owners on the morning of February 24 by barking.

From Muzychi, you could see the enemy helicopters hovering over Hostomel airport.

In the first days of the invasion, her husband joined the ranks of the Territorial Defence Forces, and she hid in the cellar with their pets. The closer the Russians came, the fewer neighbors were around. They left Alevtina the keys to their houses, asking her to feed their chickens, fish, turtles, and cats or to take care of the flowers. "I immediately wrote everything down in a notebook. I knew I would not remember anything," Alevtina recalls. "Writing in the basement where I lived with my husband and our cat during the first two weeks of the large-scale war was difficult. I did not want to accept reality and memorize those days."

But Kahidze's diary records the frightening everyday life.

"It was quiet," she says. "And I remember: that was because there were green corridors. We were just about to leave Bucha on foot."

‘Rockets’ is a record made on March 7. I noted down what they were shooting us with. We heard the missiles take off and then land somewhere far away.

‘Attack — we will all be fucking shot…’

The entries in the artist's diary are in Russian. But the word "HOME" is Ukrainian. Alevtina says that the Ukrainian language was stolen from her as her mother tongue. "My grandmother spoke Ukrainian all her life, but my mother spoke Russian. I never asked why this happened."

Kahidze was born and raised in the Donetsk region in the village of Zhdanivka, from where she moved to Dnipro at eighteen and then to Kyiv. She has participated in numerous international exhibitions, including last year's Manifesta 14, the European Biennial of Contemporary Art in Kosovo. She is a laureate of the Kazimir Malevich Art Award (2008) and, since 2018, a UN Tolerance Ambassador in Ukraine.

During the full-scale invasion, Alevtina Kahidze did not leave Muzychi, where she has lived since 2009, just as her mother, Strawberry Andriivna, did not leave Zhdanivka back in 2014. (A child from a kindergarten where Alevtina’s mother, Ludmila Kahidze, once worked called her Strawberry, and this nickname became a creative pseudonym. – Author's note)

"That's when the war started for me," says Alevtіna, who remembers recording conversations with her mother and making sketches. That's how the Strawberry Andriivna project about life in the occupied territories — with shelling, roadblocks, and lack of communication — was born. Alevtіna's mother bravely conversed with the militants of the ‘Donetsk People’s Republic,’ argued with neighbors about Russian propaganda, tended her garden, brought fruit to the mental hospital during hostilities, and sold vegetables at the farmer’s market. In January 2019, she died in line at a checkpoint of the ‘Donetsk People’s Republic.’

This project became part of the series of Alevtina’s social cartoons, "Did Everyone Who Wanted to Leave Do It?", whose creation was initiated by the ZMINA Center for Human Rights with the support of the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The aim of the cartoon is to remove discriminatory labels ‘traitors’ or ‘collaborators’ from those Ukrainians who did not leave the occupied territories. The series about Ludmila Kakhidze was drawn and voiced over by Alevtіna herself.

"My grandmother spoke Ukrainian all her life, but my mother spoke Russian. I never asked why it happened."

A common theme in Kahidze's work is the garden. No wonder she is an artist who is also a gardener. She hardly interferes in her garden’s life: the plants know what's best for them. And there are no weeds in it.

Alevtіna has another ‘garden’ — an archive that spans her entire life — dozens of folders of archival material, pictures, printouts of interviews, tickets, and contracts. Alevtіna creates the names and pictures for these folders This material you are reading will also be archived. "I believe that you need to be prepared for the role of an artist when everything that happens to you is important and attracts attention. I have no doubt: everything that happens in my life must be recorded and archived," says Alevtіna.

She depicts political events and commentaries, her conversations with foreigners abroad, reflections on Russian culture, de-colonialism, and her feelings.

While Alevtіna stayed in Muzychi, she packed her archive to move and ‘evacuate’ it. Her days were partly filled with this task — systematizing and saving the library. These archives contain her art created over the years as well as more mundane but equally important things — for example, the folder ‘Death’ with everything related to the death of her mother.

On the door of her studio, Alevtіna wrote a message to the world in English in case she did not survive: "Imitate plants as best you can — they are true pacifists on this planet." And in her interview for the documentary series Art in the Land of War, a collaboration between DocNoteFilms and Babylon'13 last year, the artist admitted she was fed up with Western colleagues with their ideas of abstract pacifism. In the fall of 2022, Alevtіna created a drawing in which two wars face each other. One is a patriotic war for liberation and against terror. The other is a war of occupation, invasion, and aggression. "When foreigners say, 'No to war,' I ask, 'To which war are you saying no?'"

According to Alevtіna, the tangible difference between Russians and other people is that they listen to us. "I have a Swiss friend who asked me why we can not give up. He said that if you thought freely, you would stay that way. He visited my residence in Muzychi. (In 2008, Kakhidze together with her husband Volodymyr Babyuk opened a private place for artists called "The Expanded History of Muzychi" in the village of Muzychi", which is still working today. – Author's note).

And so I told him that with the occupation, everything would change. I would no longer be able to make art or even just live my life. My husband and I would not simply escape with our thoughts or speak with our eyes. It sounds banal to us, but that's how it should be explained. We talked for a long time, and I saw he knew nothing about the occupation. In his mind, just as for most French people, it was like the occupation of France in World War II."

"People want to see a world without wars, but some still like to see violence."

Last year, Alevtіna participated in several major exhibitions abroad. It was an opportunity for her to speak to the world in the language of art: a parallel program of the Venice Biennale, group exhibitions in Berlin, Amsterdam, Rome, as well as in the USA, Norway, Georgia, Lithuania, and Estonia. The artist's personal exhibition, "Génération de femmes et de plantes," was held at the Embassy of Ukraine in France. Also, her works were shown in the special edition of Vogue Polska.

Through her art, Kakhidze explains complex issues in simple language. During a performance in Paris, she gave the example of a gardener whose snails had eaten all the lettuce in the garden, leaving him with nothing to eat. "Then I asked the audience if he would blame certain snails in this case," Alevtina says. "No, he would blame all of them. It is the same now with our attitude toward the Russians. What do we want? That they do not exist. But at the same time, I want them to admire us. In fact, why not? But they will not be able to do that. Although they might admire that we succeeded with the revolution, that we are also trusted in society."

She asks me if I believe in a world without war. I say no. After all, the dark power will still drive certain people to aggression — the only question is how quickly we can stop it and prevent long wars. Alevtіna, on the other hand, believes that progress is natural: "I believe that the world is changing. If it had not changed, I would not be sitting here because I would have been on the bondhold. Vaccination, for example, has greatly prolonged our lives. People want a world without wars, but some people still like to see violence. Once, a curator asked me what she could do for me now. I replied, ‘Study the history of Ukraine.’"

Text: Oksana Semenyk

Photo: Vasylyna Vrublevska

Video: Slava Davydov

Video interview: Maryna Shulikina

Makeup and hair: Anna Zhadko, Alex Chekrizova

Translation: Yulia Vervoort, Hanna Leliv

About the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation’s Museum of Civilian Voices

The Museum of Civilian Voices is the world's most comprehensive collection of stories of civilian victims of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Since 2014, the Foundation has collected the stories of thousands of Donbas residents in its unique online museum. Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the museum has become a chronicle of the tragedies of all the country's residents. The museum's mission is to create a reliable source of first-hand information about the lives of civilians in the conditions of war. Follow the link to hear more stories of Ukrainians affected by Russia's war against Ukraine.