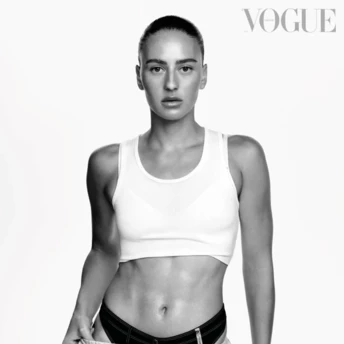

"Everything that medical volunteers do is about life," says Natalia Lelyukh, a gynecologist, medical volunteer, writer, and blogger. Before the full-scale invasion, she was the main popularizer of science on women's health. After February 24, 2022, she has taken on an emotionally heavy and physically demanding burden. She travels around the de-occupied territories offering medical assistance to anyone who needs it. In an interview with Ukrainian Vogue, Natalia tells why civilians' stories should be heard, why words are sometimes powerless, and hugs are necessary, and why it's worth asking for help.

This material was produced with support from the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation's Museum of Civilian Voices. It continues the series of video interviews in which our heroes and heroines tell their war stories for the world to hear.

Before the full-scale invasion, Natalia Lelyukh was a well-known gynecologist and moderator of the Women's Club. She spoke about women's health in a simple and accessible way. Currently, she is a volunteer doctor—collecting and sorting medicines and delivering them to the de-occupied territories; counseling people already on the verge of despair, and restoring their faith.

"I woke up on the 24th. I could already hear explosions. I did not have an emergency bag. I did not have a plan. My daughter was somewhere near Hostomel at a friend's house. I woke her up with a phone call and went to get her," Natalia says. The trip back to town took several hours. A plan was still needed. One of the urgent tasks was to get the son and daughter to a safe place. "The hardest part for me at that time was explaining to them why I was staying here. Why I was not going with them," Natalia says.

The next day she was just cleaning the house. Methodically, she put things together, cooked food, and did some washing and cleaning—as a kind of meditation. "I needed to clear my mind. To go back to scratch, to understand what to do next," she says. For the first time, she felt that life was finite. "I just realized that I could die. That everything has become fragile. That there are no plans—and can not be any. There was this moment and a clear understanding of the end. Not even fear. The awareness of death," says Natalia.

The next time she saw her daughter was in June. Her son—in May. Then she had no idea what lay ahead. She just started searching for opportunities to help. She called Lesya Lytvynova, co-founder and director of the Svoyi charitable foundation, which supports cancer and palliative care patients. Lesya had already signed up for the Territorial Defence Forces. "I was shocked," Natalia recalls. "But Lesia, you’re breastfeeding a baby!" I said. Natalia then tried to help at Lesia’s foundation but realized she could not make much of a difference there. So, she called another volunteer, Tata Kepler. Tata said, "There is a container with humanitarian aid. Come, let’s sort it out." That's how it all started.

She felt emotionally unavailable for the first time when she realized she could not take off her uniform. "It has become my protection. My talisman. How could I wear anything else? Dresses? Civilian clothes? No way. I was constantly unpacking boxes, unloading, and packing something. My whole life revolved around this uniform. Without interruptions or rest," she says. That was when she first consulted a therapist. Not for her own sake but to be able to continue to do what was needed. The second time she realized she was traumatized was when she saw an airplane on the train to Krakow: "I just dropped to the ground. The people around me froze. The plane was a threat to me. But I was completely safe."

Natalia says that we are all very traumatized, regardless of where we are: under shelling, in our homes during an air raid alert, or in safety abroad. "I still see the eyes of the women in front of me who come to me for counseling or whom I meet at the Women's Club events in Europe. There is an incredible fatigue in their eyes. Weariness mixed with a feeling of guilt because no matter how much you do, no matter how long you have been working for the country, it always seems that it's not enough, not enough, not enough because you are still alive while others are dying for your right to live," she says.

Sometime in June, she resumed seeing patients. "We went to small de-occupied villages, to destroyed hospitals where no one really went," Natalia says. "People there have already lost hope of being heard. I’m needed there. Of course, I can not cure a stroke right away, and I can not save everyone, but I make people believe that help is on the way, that they have not been forgotten, and that a doctor will come and listen to them and just hold their hand, give them medicine and useful advice. That's part of what doctors should do. And I do it, too."

During this time, much has changed. Her relationship with the man who had been close to her in recent years ended. "Nothing was wrong. I simply realized that I was no longer in a hurry to get home at the end of the day, that there was nothing there to give me strength," Natalia admits. "There were two parallel lives of two people, each with their own goals and dreams. This relationship has lost its meaning. Why should it drag on?" They went their separate ways, as did many other couples during the war.

At the same time, she says that without the war, she would not feel like a woman. "It was the war that gave me that realization. Here I am, sitting in stockings, with dreadlocks on my head, saying to myself, "Natasha, seriously? Do you actually know how old you are? Dreadlocks? Stockings? What are you even thinking of?" And then I respond to myself, "If not now, when? When should I live, if not now?"

She believes that the Maidan is the cause of everything. Natalia says, "It was then and there that my path to the person I am today began." On the day of the shooting, she was not on the Maidan. Natalia was on duty at the hospital and followed the news stream non-stop. People on the Maidan were constantly looking for doctors. "I’m a doctor. I should have been there, and I was at work delivering babies, delivering new life, while I could’ve been saving what already existed," she says. That thought has haunted her ever since, and she says it's only now that she's been able to work through that guilt, at least a little bit. "Because I’m a doctor, Olya, I’m a woman, a mother, a wife, a lover, a homemaker, but first of all—a doctor. Doctor Natasha. That's who I am. And right now, I’m doing what I have to do. That's what I am here for, where I’m needed most, where my experience is most useful."

Text: Olha Rudneva

Photo: Vasylyna Vrublevska

Grooming: Anna Zhadko

Video and photo report: Slava Davydov

Makeup: Daria Zhadan

Video interview: Alyona Ponomarenko

Translation: Yulia Vervoort, Hanna Leliv

About the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation’s Museum of Civilian Voices

The Museum of Civilian Voices is the world's most comprehensive collection of stories of civilian victims of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Since 2014, the Foundation has collected the stories of thousands of Donbas residents in its unique online museum. Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the museum has become a chronicle of the tragedies of all the country's residents. The museum's mission is to create a reliable source of first-hand information about the lives of civilians in the conditions of war. Follow the link to hear more stories of Ukrainians affected by Russia's war against Ukraine.